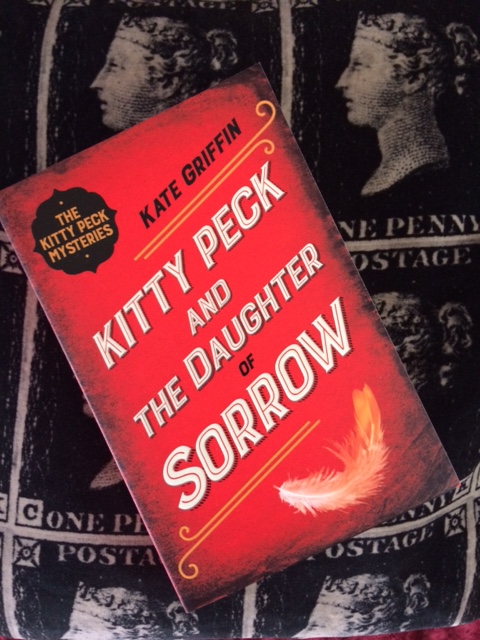

This month Kitty Peck and the Daughter of Sorrow, the third book in my romping melodramatic murder mystery series, was published by Faber and Faber. To mark its release, I thought I’d let you into a secret…

We often see Victorian women as meek, repressed creatures, their spirit crushed by complex whalebone corsetry and the iron will of men. Of course, the truth was different, but the suffocating stereotype persists.

Researching the world of Victorian music hall – and most particularly women in music hall – for my Kitty Peck series was a revelation, blowing away those dusty tropes with a blousy, brazen blast of fresh, but not entirely fragrant, air.

In a world where women often had limited control over their lives and decisions, it was fascinating to learn that working ‘the halls’ could offer both financial and artistic freedom.

Don’t be deceived by the cheery songs and bawdy humour, it was a hard life – and it could be a tragic one (alcoholism, consumption, venereal disease and prostitution were always somewhere on the bill), but this was also a place where women could achieve independence and autonomy, if they made the right choices.

The last years of the 19th century were a boom time for women in music hall. In the week before Christmas 1891, 76 sketches running in London starred female comics. I was surprised to discover not only that female performers were so numerous, but also that they outnumbered the men (at the same time 74 were male). I was heartened by a Victorian audience’s appreciation of funny females. In comparison, the ratio of women to men in comedy today is depressing.

I’m often asked if I based Kitty on a particular performer. The short answer is no, she’s entirely her own person, but a more honest reply would acknowledge the women whose fascinating stories I discovered as part of my research.

Tell truth, as Kitty often says, I suspect my lead character owes much to the remarkable Jenny Hill, also known as the ‘Vital Spark’.

Although she’s not well-known today, Jenny Hill was a hugely popular and pioneering performer, famous for her salty back chat and overtly political performance. The Boy I Love is Up in the Gallery was her song originally, although it’s now associated with Marie Lloyd, probably the most famous female music hall star.

There’s not room here to do Jenny justice, so a canter through her story will have to serve.

Born in 1848, Elizabeth Jane Thompson (her real name) was the daughter of London hackney cab driver. The family was poor and ‘Jenny’ was sent out to work as a child performer. Her stage début was made at the age of six or seven, when she performed as the back legs of a horse in the pantomime Mother Goose at the Aquarium Theatre in Westminster.

In 1862, when Jenny was 14, her father Michael apprenticed her to a publican in Bradford whose spit and sawdust establishment was typical of the edgy, rowdy venues where music hall began.

It wasn’t a glamorous life. The waif-like girl (Jenny was always described as small and apparently frail) began work at 5am polishing the bar and pewter, washing glasses, scrubbing floors and bottling beer until her performances began at noon. She was then required to sing for the customers until the pub closed at 2am.

It must have been unbelievably harsh and dangerous work for a 14-year-old, even one as resilient as Jenny, and these early days were to have severe consequences for her health in later years.

It’s easy to speculate that the teenager might have sought comfort and perhaps protection in such a hostile environment. Certainly, at an early point in her performing career Jenny married an acrobat whose glorious stage name was Jean Pasta (actually, and more prosaically, she became Mrs John Wilson-Woodley.)

The marriage was short-lived. Jenny was barely out of her teens when the inglorious ‘Pasta’ deserted her, leaving her destitute with three children to support, including a baby girl, who later became music hall performer Peggy Pryde.

This could easily have been the beginning of a sad and desperately familiar tale, but the enterprising Mrs Wilson-Woodley seized her own destiny. She auditioned for a try out at the London Pavilion and her song stopped the show. The popular entertainer George Leybourne, famous for the music hall standard Champagne Charlie, is said to have led her, trembling, back into the limelight for an encore.

Jenny’s career as a female serio-comic took flight. For those unfamiliar with the term, these were performers whose acts included comic and serious songs and sketches, interspersed with patter and audience interaction. They relied heavily on satirical songs and their material can be seen as an embryonic form of stand-up comedy.

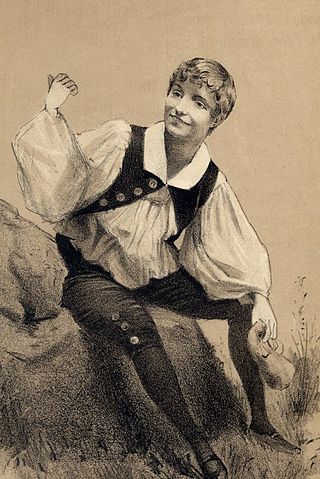

A versatile performer, Jenny sang, danced, gave her punters ‘the old chat’, and had a popular routine as a male impersonator – a music hall favourite and a theme I play with in the Kitty Peck series.

Jenny Hill as a principal boy

Jenny Hill as a principal boy

By 1871 she was earning the very respectable sum of £6 a week at the London Pavilion. The theatrical agent Hugh J. Didcott gave the pert, witty and vivacious performer the sobriquet ‘The Vital Spark’, which she used throughout her career.

Jenny swiftly became independently wealthy, buying an estate, The Hermitage, in Streatham, where she famously entertained in starry style. She was entrepreneurial too, becoming the proprietor of at least three establishments, while still performing comedy and musical routines and appearing as a popular principal boy. As a name, she was occasionally booked to act in straight plays as well.

Jenny remained at the peak of her career until 1890, enjoying top-billing at music halls in London and the northern provinces. Appropriately, one of her best-loved songs was, If Only I Bossed the Show.

She clearly did.

Not to put too fine a point on it, Jenny became wealthy. An archive newspaper report from 1881 records that, on average, an actress in the ‘legitimate’ theatre would receive about two or three pounds a week, to live off and buy her own costumes for the shows she appeared in. At around the same time, Jenny Hill is documented to have received £80 for 12 nights at single venue, and (separately) to have appeared at three to four different halls a night, earning £30 for every performance.

(NB: It was common for successful music hall performers to perform at multiple venues in one evening. Rattling between halls in a hackney cab, they often resorted to alcohol and opiates to keep their strength up, and in winter to ward off the cold. As a result, many performers became addicts or alcoholics or both.)

A native cockney, Jenny was clearly a shrewd player. Early on, when she was engaged to appear at London’s Thornton’s Music Hall, the manager was shocked by her up-front demand for a fee of £40 for just one week of appearances. She was adamant that £40 was her ‘very lowest’. His telegram confirming this (then) enormous sum was subsequently displayed by Jenny herself, as an advertisement for a ‘no-expense-spared show’.

It seems that in addition to her talent as a performer she was a savvy early adopter of the art of self-promotion!

She was also something of an impresario and theatrical property magnate, although, admittedly, these ventures were less successful than her performing career.

In 1879, aged 31, Jenny purchased the Star Music Hall in Bermondsey and from July 1882 to 1883 she also kept a pub in Southwark. In July 1884 she bought the Rainbow Music Hall (later renamed the Gaiety Theatre), Southampton. Opening in September 1884 after refurbishment, it burned down in December of the same year – something I stole for Kitty Peck and the Child of Ill Fortune.

An established star in Britain, Jenny even appeared in vaudeville in New York. Punters across the Atlantic had trouble with her cockney slang, however, and she was never booked to return. This is something I can sympathise with. When I asked my publisher why the American rights to the Kitty Peck books hadn’t been sold I was told that it was probably due to the ‘narrative voice’. Kitty relates her story in a strong cockney idiom.

By 1889, the poverty and hardship of Jenny’s early life were taking their toll and she was forced to cancel a number of theatrical engagements due to ill health. Following the death of her estranged husband in 1890, she married music hall manager Edward Turnbull, but by this time it was clear that she was suffering from consumption. Advised by her doctors to go to a warmer climate for the winter, she accepted an invitation to appear in Johannesburg, arriving there in December 1893.

By then her health was so poor that she could only be taken onto the stage in her wheelchair. There are touching reports that she did little more than shake hands with members of her audience. Returning to Britain in May 1894, she moved to the more moderate climate of Bournemouth for her health.

Like many music hall performers, Jenny Hill was relatively short-lived. She died in 1896 – aged just 48 – at the London home of her daughter, Peggy.

Jenny’s story has some very modern resonances. The press took a salacious delight in her life, loving her and loathing her in a way that is all-too familiar. She reminds me of a soap star or reality TV personality hounded by the ‘red tops’.

Lurid newspaper reports repeatedly insinuated that the stage was ‘bad for her health’ – code for ‘she’s an alcoholic’. She was often referred to as ‘a clever little thing’ (simultaneously patronising and suggestive), and it was consistently implied that her estate in Streatham was bought for her by someone else, hinting at the existence of a secret male lover, because, of course, no low-born woman could afford to pay for something like that herself.

Jenny counteracted these barbs with adverts (like the one mentioned above), where she declared exactly how much she was being paid, specifically to demonstrate that she was earning this money for herself and by herself.

Performer Fanny Leslie, one of Jenny’s contemporaries, said: “I like to make my own successes, and I work hard to earn them, and I don’t like to be robbed of the fruits of my labour by other people’s incompetence. On the halls I choose my own songs, arrange my own business, and if I fail to make a hit it is a satisfaction to know that no one is to blame but myself.”

In Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the bawdy Wife of Bath – who surely would have been a music hall natural – reveals that what women want most is ‘maistrie’ – mastery and control of their own lives.

Women like Fanny and Jenny understood that if they worked the halls, they could achieve this. Yes, as performers – and worse still female performers – they were still regarded as morally and socially suspect, but if they made it they were adored by the masses, earned vast sums, travelled the world and experienced lifestyles that would never normally have been theirs.

When you add to this the appeal of a great many fringe benefits in the form of gifts from besotted admirers – diamonds in Jenny’s case – I think it’s fair to say that really, they probably didn’t give a stuff what people thought.

Put bluntly, women working the halls didn’t have a reputation to lose and so much to gain.

Jenny Hill’s colourful, theatrical story is one of a Victorian woman who took control of her own destiny. I’ve stolen elements of her ‘vital spark’, her ‘back chat’ and her entrepreneurial flair for Kitty.

In return – and I admit it’s a poor one – I’ve visited her grave in the gorgeously gothic Nunhead Cemetery in South London where she is buried along with many other music hall performers.

(NB: music hall artists were often buried in non-conformist cemeteries away from ‘respectable’, reputable people. I think Jenny Hill would laugh at that.)

Jenny Hill

Jenny Hill

Kitty Peck and the Daughter of Sorrow is published by Faber and Faber.

It is available from bookshops and from Amazon

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Kitty-Peck-Daughter-Sorrow/dp/0571315208

Others in the series:

Kitty Peck and the Child of Ill Fortune (book 2)

https://www.amazon.co.uk/d/cka/Kitty-Peck-Child-Ill-Fortune-Kate-Griffin/0571310850

Kitty Peck and the Music Hall Murders (book 1)

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Kitty-Peck-Music-Hall-Murders/dp/0571302696

I always hold in having it if you fancy it

If you fancy it, that’s understood

A little of what you fancy does you good.